A

SHORT HISTORY OF CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE:

German

French

Italian

Japanese (coming soon)

Polish

Spanish

Czech

English

From

the Thirty Years’ War to Prince Eugene of Savoy

The European history of the 17th century was characterized

by two main conflicts, namely by the clashes between Protestants

and Catholics, which affected almost all European countries

during the Thirty Years’ War (1618 - 1648), on the one

hand and by the continuing struggle against the Ottomans,

who tried to extend their territory from the Balkans towards

the west during the second half of the century, on the other.

In the west of the continent, France, ruled by King Louis

XIII and King Louis XIV, tried to gain supremacy in Europe

and to reduce the power of the Habsburgs in Spain as well

as in Germany. As a consequence - apart from the wars between

France and Spain - France started to conquer territories along

the Rhine and formed an alliance with the Ottomans. England

and the Netherlands, the new economic powers, also took part

in these events. During the fight for freedom of the Dutch

against the Spanish a new art of fencing had developed as

a consequence of a military reform of the Orange, which, mainly

based on expert training, permitted troops greater manoeuvrability

and stability.

Until the beginning of the 17th century the imperial armies

varied in equipment and were only hired for the duration of

a campaign. Now they formed a permanently paid standing army.

Due to the lack of money of the Emperor the army was partly

financed by so-called war-contractors like generalissimo Albrecht

Duke of Mecklenburg, better known as Wallenstein. The peace

treaties of Osnabrück and Münster ended the Thirty

Years’ War in 1648.Compared to other Central European

armies the Ottoman army was organized completely different

and equipped with strange weapons like bows and arrows; it

had been pushing forward to the west since the 60ies of the

17th century and was defeated on August 1, 1664 at Mogersdorf

near St. Gotthard, situated on the river Raab.

But it was not until 20 years later that the advancement of

the Ottomans entered a crucial phase, as the Turkish army,

lead by Grand Vizier Kara Mustapha, marched up in front of

the gates of Vienna in July of 1683. The threat of the imperial

capital and royal residence threatened the whole of Central

Europe. And it was not until September 12, 1683 that Vienna

was relieved by a united army of imperial and Polish troops.

This was the turning point as well as the beginning of the

repulsion of the Turkish army. As a result of the decisive

battle at Zenta, situated on the river Theiß, (1697)

and the peace treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 a large part of

Hungary and all of Transylvania could be regained.

These successes were mainly due to the military genius and

diplomatic skills of Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663 - 1736),

who therewith laid the foundation of Austria’s big-power

status during the first third of the 18th century.

The

18th Century (until 1790)

The 18th century was a time of continuing power struggles

in Central Europe, which were interrupted only by the French

Revolution. The main concern was the struggle for dominance

of France, England, Austria, Russia and Prussia. The extinction

of the Casa de Austria in Spain in 1700 (death of Charles

II) caused a huge power vacuum in Central Europe as well as

overseas.

During the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) Austria

and France struggled to gain supremacy over the regions and

provinces temporarily without a sovereign. In spite of the

glorious victories by the imperial troops which were led by

Prince Eugene of Savoy this struggle was finally resolved

by England’s partisanship. After first supporting the

Habsburgs, England feared a Habsburg hegemony and enforced

a splitting up of the Spanish heritage between the two belligerent

rival powers. Emperor Charles VI obtained the southern part

of the Netherlands and all former Spanish properties in Italy,

while Philip of Anjou became King of Spain and sovereign over

the Spanish overseas territories.

The events on the Balkans were, however, no less fundamental

and of serious consequences. Prince Eugene’s victories

at Peterwardein and Belgrade during the war against the Turks

from 1716 to 1718 secured the biggest extension for the Habsburg

Monarchy as well as its rise to the status of a major power

in Europe. The War of the Polish Succession then followed

between 1733 and 1738.Emperor Charles VI lost almost all of

his possessions gained in 1718 during another war against

the Turks from 1737 to 1739, which was fought in alliance

with the rising power Russia.

By means of the Pragmatic Sanction the Emperor tried to protect

the right of inheritance of his daughter Maria Theresia against

the claims of other European powers, but it was all in vain.

During the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) Maria

Theresia had to defend her heritage against almost all neighboring

sovereigns.Her main opponent was King Frederick II of Prussia,

to whom - as the only loss of territory - she had to cede

Silesia in the end. As a result Prussia also gained the status

of a major power in Europe.

A new conflict (the so-called Seven Years’ War from

1756 to 1763) between Austria -initially supported by Russia

and France - on the one hand and Prussia on the other flared

up soon; in the end Frederick II retained his hold on Silesia.

This war culminated in a total reverse of the previous system

of European alliances, and on top of it had global political

consequences, too: during the War of the Spanish Succession

England had already replaced France in the trade with America,

and later on it captured all former French colonies in India

and North America. England thus managed to gain the status

of a world power. The end of this century saw Austria’s

last war against the Turks from 1788 to 1791, in which Emperor

Joseph II - in alliance with Russia - proved to be victorious

and in 1789 field marshal Laudon succeeded in recapturing

Belgrade.

Austria and Europe 1789-1866

From the French Wars until 1848

Towards the end of his reign, Joseph II waged another war

against the Turks that again ended with capture of Belgrade

(1789). This victory was more important to Austria than the

French Revolution that took place at the same time. In Paris,

on 14 July 1789, an angry crowd stormed the Bastille, the

state penitentiary, a symbol of the much hated rule of King

Louis XVI. In April 1792, France declared war upon Austria.

The Habsburg Monarchy formed the so-called First Coalition

with Prussia and England.

The ensuing war lasted until 1797 and ended with the defeat

of the allies; for Austria it meant the loss of its dominions

in the west of Europe and of Lombardy. It gained Venetia,

however. In this war, Napoleon Bonaparte had increasingly

distinguished himself as a French general. Austria relied

on the military talent of Archduke Charles, the brother of

Emperor Francis II., who had achieved a number of victories,

including Würzburg in 1796.In 1799, the Secon Coalition

War broke out. It was conducted primarily by Austrians and

Russians against France. The Peace of Lunéville concluded

this war. France under Napoleon, who had crowned himself Emperor

of the French in 1804, very clearly aimed at dominating Europe.

As a consequence, Austria and Russia once again declared war

on France in 1805. It ended with the battle of Austerlitz

(Southern Bohemia) and the Peace of Pressburg (Bratislava).

Austria had to cede the Tyrol to Bavaria which was allied

with France. In 1806, Francis II. (1768-1853) laid down the

crown of the Holy Roman Emperor. He then ruled as Francis

I. of Austria. In 1809, the Habsburg monarchy attempted an

independent initiative. In spite of the long-lasting conflict

with France and its allies, Austria’s willingness to

make sacrifices seemed undiminished. National enthusiasm steadily

increased. Among other things, the establishment of the Landwehr,

a kind of territorial reserve, was testimony to this.

In the campaign, which lasted from April until July, Archduke

Charles won the Battle of Aspern (21./22. May, 1809), but

lost the Battle of Deutsch-Wagram (5./6. July, 1809), which

decided the war. In the Peace of Schönbrunn, Austria

again had to accept heavy territorial losses. Nevertheless,

the Habsburg Monarchy joined a coalition of Russians, Prussians,

Swedes, and the British. Napoleon’s fate was decided

in the Battle of Leipzig between 16 October and 19 October,

1813. At the end of March 1814, the allies arrived in Paris,

and Napoleon abdicated. The Congress of Vienna, which took

place between November 1814 and June 1815, served the purpose

of reorganizing Europe.

Napoleon’s attempt at restoration, which ended with

his defeat in the Battle of Waterloo and the exile of the

French Emperor, was all but an entr’acte. On 20 November

1815, the Second Peace Treaty of Paris was signed. Only a

few years after the Congress of Vienna, however, many European

countries were troubled by revolutionary movements caused

by major social and national problems. On 13 March, 1848,

revolution finally broke out in the Austrian Empire as well.

In Prague, the revolutionary movement was violently crushed.

In Vienna, the rebels succeeded in forcing the Imperial and

Royal troops stationed in the city to leave. It was not until

October that the Imperial city was recaptured by Prince Alfred

Windischgrätz and Feldmarschall-Leutnant Count Joseph

Jellacic, using enormous military means. In Hungary and Italy,

though, the situation remained extremely tense.

Field

Marshal Radetzky and his Time

In

1848, the outbreak of revolution once again seemed to form

the prelude to the disintegration of the Austrian Empire.

The Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont took the revolutionary events

in Lombardy and in Venetia as an opportunity to declare war

on Austria. In Hungary, revolutionary and national forces

formed and began to march towards Vienna. Only after deploying

all available military forces was it possible to put down

the revolution and conduct war on two fronts. The engagement

thereby sometimes took on the characteristics of a blitzkrieg.

Field Marshal Radetzky, the supreme commander in the area,

defeated the Sardinian-Piedmontese army in a number of skirmishes

and battles, and called a truce which was renounced by Sardinia

in 1849.Once again Radetzky achieved victories at Mortara

and Novara, which brought about peace at least for a few years.

Yet Hungary was different. Fighting there dragged on all winter

and most of the year 1849 and could only be stopped through

the cooperation of Austrian troops with a Russian contingent.

On 2 December, 1848, Emperor Ferdinand I abdicated the throne

in favour of his nephew, Francis Joseph.

Thus began the Francisco-Josephinian era, which lasted for

68 years.After the victories in Italy and Hungary, the young

Emperor strove to consolidate the empire again, and to establish

a strong, centralized government. Francis Joseph tried to

continue using the Austrian army as an instrument to maintain

or restore order in Europe.In 1864, Austria and Prussia combined

to go to war against Denmark. The conflict was about the two

German-speaking principalities of Schleswig and Holstein,

both of which were under Danish administration. The victors

of this war, Austria and Prussia, quarreled over the two territories.

On 8 April, 1866, Prussia formed a league against Austria

with the Kingdom of Italy. Under the command of Archduke Albrecht,

the southern army of the Austrians was victorious near Custoza

(south of lake Garda) on 24 June, 1866. But the war was decided

in the north.The Austrian Army under Feldzeugmeister Ludwig

von Benedek suffered a devastating defeat near Königgrätz

(Hradec Králové, east of Prague) on 3 July.

The Peace Treaty of Prague pushed the Austrian Empire out

of the German Confederation for good. It kept only its positions

in the eastern part of central Europe and in south-eastern

Europe.

Emperor Franz Joseph and Sarajevo (1867-1914)

As

a result of Austria’s defeat in the war against Prussia

in 1866 the Habsburg Monarchy lost much of its influence in

shaping the policy of the German states. Thus it was of utmost

importance to create a permanent political structure for its

own provinces. The most pressing problem was the Hungarian

question. Since the revolutionary wars of 1848 and 1849, the

provinces of the Hungarian crown, namely Hungary, Slovakia,

Croatia andTransylvania, had partly lost their former liberties

and came under strict Hungarian civilian and military control.

But this should not last.

In 1867, after lengthy negotiations, the socalled „Compromise

of 1867“ (Ausgleich) could be reached in which the relationship

between the provinces of the Hungarian crown and the rest

of the Empire was completely redesigned.The Habsburg Monarchy

was henceforth divided into two parts, namely the Austrian

provinces (Cisleithania) and the provinces of the Hungarian

crown (Transleithania). Each half was supposed to have its

own government and its own regional parliaments. After 1867

there were only three areas which were handled by both parts

in common, namely foreign affairs, finances and defense. And

only for these three sectors supranational ministers were

appointed.

This „Compromise of 1867“ brought the most far-reaching

consequences for the army. In those days the „k.u.k.“

(imperial and royal) army and the „k.u.k. (imperial

and royal) navy were formed. In addition to that the „k.u.“

(royal Hungarian) Honvéd was formed in the Hungarian

part of the Dual Monarchy and the „Imperial and Royal

Yeomanry“ (k.u.k. Landwehr) in the Austrian half. The

period of peace between 1867 and 1914 was interrupted only

by one bigger military event, which is known in Austria’s

history as the campaign of the occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

in 1878. Bosnia and Herzegovina, former provinces of the Ottoman

Empire, were then occupied by Austro-Hungarian troops.

In 1908 these territories were fully annexed. Apart from that

the Austro-Hungarian Empire participated only indirectly in

the European power game. Austria entered an alliance with

Germany in 1879 which was extended to Italy in 1882. Thus

we speak of the „Dual Alliance“ and of the „Tripartite

Alliance“. From 1908 onwards the Austro-Hungarian Empire

was more and more involved in the conflicts in the Balkans.

After several decades it became apparent that the „Compromise

of 1867“ had not brought about a completely satisfying

solution for the Habsburg Monarchy’s problems.

The demands of the altogether eleven bigger nationalities

of the Habsburg Monarchy, could obviously only be met by means

of a completely new and radical restructuring of the Empire.

Hopes that this goal might be achieved were, above all, placed

in the heir apparent to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

Emperor Franz Joseph had, however, not assigned significant

political responsibilities to his nephew restricting him to

a merely military role which included supreme command of the

armed forces in case of war. On Sunday, June 28, 1914, while

visiting Sarajevo, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were

assassinated by a Serbian nationalist.

World

War I and The End of the Habsburg Monarchy

For

Austria-Hungary Serbia was the only one to be blamed for the

assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in

Sarajevo, and the only consequence for this could be the subjugation

of Serbia. As a result Austria-Hungary made a number of ultimate

demands on Serbia, which induced Serbia to mobilize and Russia

to lend them political support. Thus, a limited local conflict

developed into a war against an alliance which at the end

of July 1914 saw Austria-Hungary, the German Reich and later,

at the end of October 1914, also the Ottoman Empire as the

"Central Powers" (Mittelmächte) on one side

and Serbia, Russia as well as France and Great Britain, both

allies of Russia, as "The Entente" on the other.

At first the emphasis of all military actions of Austria-Hungary

was concentrated on the Balkans and on Galicia, while the

German Reich set out to overthrow France. But Austria-Hungary

was unsuccessful in Serbia and Galicia as were the Germans

in the West. Already at the end of 1914 Austrians and Germans

had to take every effort to stem the tide of the advancing

Russian army. The danger from the East was not over until

after the Austrian offensive at Tarnòw Gorlice in May

of 1915, the same month in which Italy declared war on the

Habsburg Monarchy.

In spite of all these set-backs for Austria-Hungary and the

German Reich, several important military victories could be

claimed. Bulgaria joined in as an ally of the Central Powers

by autumn of 1915. Serbia was defeated and the Central Powers

were able to establish a land bridge to Turkish territory.

In a first offensive, out of South Tyrol, at the beginning

of 1916, the Central Powers failed to defeat Italy. This resulted

in a series of battles of attrition along the Isonzo frontline

until the end of 1917. In the East the Russian army was forced

to withdraw in 1917 because of the Russian Revolution. This

lead at first to a ceasefire and then to the conclusion of

the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

The defeat of Romania, which in September of 1916 had also

declared war on the Central Powers, was likewise a success.

Another tactical victory was the l2th battle at the Isonzo

in October and November of 1917 which was won by the Austrian

and German armies. But the current military situation obscured

the view on domestic political decay inside the German Reich

and particularly the increasingly chaotic conditions within

the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The lack of food and collapsing

distribution reached catastrophic dimensions in 1917. Austria-Hungary,

already having had severe problems of balance with its 17

different nationalities during peace time, was now threatened

to fall apart.

Emperor Karl I, successor of Emperor Franz Joseph after the

latter's death in November 1916, intensively tried to reach

a peace agreement, but could not succeed. In 1918 strikes

and mutinies began to gain ground. In a last offensive, which

started on June 15, 1918, Austria-Hungary again desperately

tried to bring about a military decision, but this attempt

failed at the Piave river. In autumn of 1918 the Habsburg

Empire began to dissolve and the armed forces disintegrated

rapidly. On November 3rd, 1918 an armistice agreement was

reached and signed by Austria-Hungary at the Villa Giusti

in Padua. At that time the Habsburg Monarchy had already been

split into various national succession states and nations

- Europe had forever changed.

back

to top

CEE

PORTAL LIVING HISTORY SERIES POSTERS:

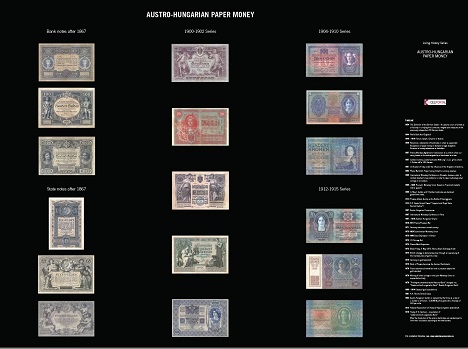

Poster Austro-Hungarian Paper Money (incl. timeline)

Size:

91 x 68 cm (35.5 x 26.5 inches)

The Poster shows the particularly beautiful banknotes from

the period between 1867 and 1918. By designers such as Gustav

Klimt and Koloman Moser.

An ideal gift for anybody with an interest in European (monetary)

history.

Highly decorative

Condition: New/Original/Sealed Packaging

Premium Reprint

Language: English

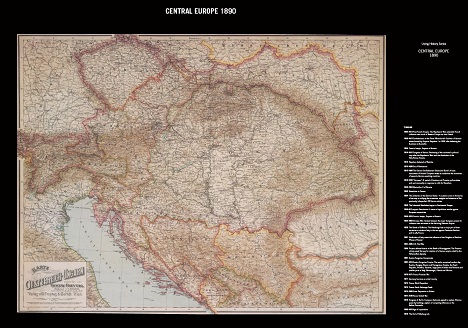

Map

of Central Europe 1890 (Austro - Hungarian Empire, Habsburg

Empire)

Size: 91 x 68 cm (35.5 x 26.5 inches)

An ideal gift for anybody with an interest in European history.

Highly decorative

Condition: New/Original/Sealed Packaging

Premium Reprint

Language: English

|